technology

technology

[ad_1]

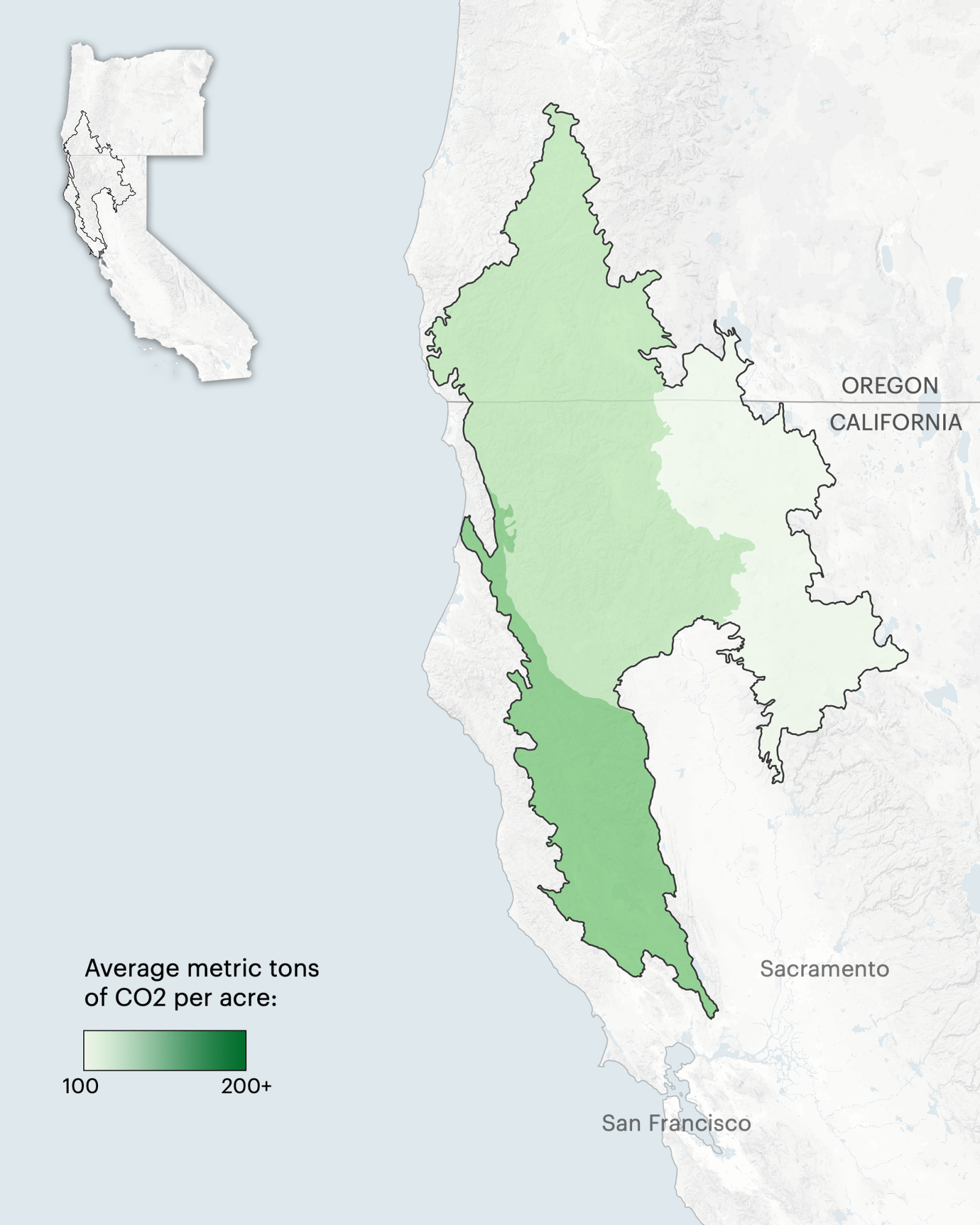

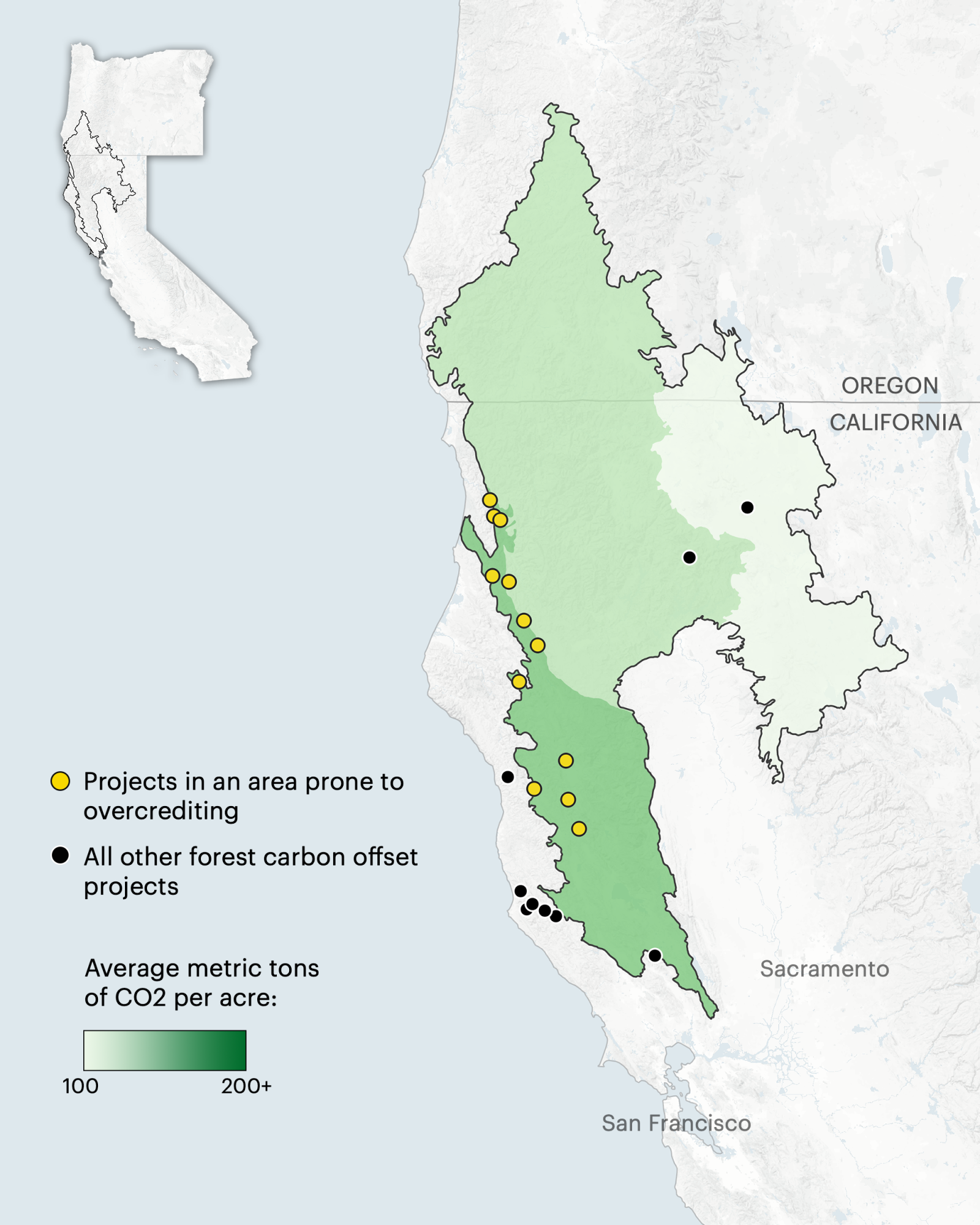

One way the California Air Resources Board determines the number of credits for a project is by comparing the carbon stored in that forest against regional averages. The bigger the difference between the two, the more credits, and money, landowners can earn.

Sources: California Air Resources Board, Forest Inventory and Analysis Program Credit: Lucas Waldron, ProPublica

Preserving especially carbon-rich forests is good for the climate, in and of itself. But when the trees in the project area bear little resemblance to the types of trees that went into calculating the regional average, it exaggerates the number of credits at stake, CarbonPlan’s study found.

Mark Trexler, a former offsets developer who worked in earlier US and European carbon markets, said the board should have anticipated the perverse incentives created by its program.

“When people write offset rules, they always ignore the fact that there are 1,000 smart people next door that will try to game them,” he said. Since the board set up a system that “incentivizes people to find the areas that are high-density, or high-carbon, that’s what they’re going to do.”

To estimate the extent of overcrediting in California’s program, CarbonPlan calculated its own version of regional averages for each project. The researchers drew on the same raw data used by the Air Resources Board, but only used data from tree species that more closely resemble the particular mix of trees in each project area.

In total, 74 such projects had been established as of September 2020, when CarbonPlan began its research. CarbonPlan was able to study 65 projects that had enough documentation to make analysis possible. All received credits for holding more carbon than the regional average.

The researchers found that the vast majority of projects were overcredited, but about a dozen would have received more credits under CarbonPlan’s formula. Those included two New Forests projects, which would have earned as much as an additional 165,000 credits.

The news organizations sent officials at the Air Resources Board a copy of the study and its detailed methodology weeks before publication. Clegern declined multiple requests to interview board staff and responded only in writing.

He did not address CarbonPlan’s calculations. “We were not given sufficient time to fully analyze an unpublished study and are not commenting further on the authors’ alternative methodology,” he wrote.

The outside scientists who reviewed the research on behalf of ProPublica and MIT Technology Review praised the study.

“It’s a really analytically robust paper and it answers a really important policy question,” said Daniel Sanchez, who runs the Carbon Removal Laboratory at UC Berkeley. While close observers are well aware of numerous problems with California’s forest offset rules, “they’re revealing a deeper set of serious methodological flaws,” he said.

None of the reviewers pointed out any major technical or conceptual flaws with the paper, which has been submitted to a journal for peer review.

In early 2015, an offsets nonprofit hosted a webinar highlighting how Native American tribes could participate in California’s program.

One speaker was Brian Shillinglaw, a Stanford-trained lawyer and managing director at New Forests who oversees the company’s US forestry programs. The company manages the sale of carbon credits, sells timber, and on behalf of investors manages more than 2 million acres of forests globally, a portfolio it values at more than $4 billion.

New Forests also manages its affiliate, Forest Carbon Partners, on behalf of an institutional investment client it declined to name. Forest Carbon Partners finances offset projects and shepherds landowners through the process of applying for California’s offset program.

“The bottom line is the California carbon market has really created a significant new commodity market,” Shillinglaw said during his presentation. He said the program is something “many Native American tribes are very well situated to benefit from, in part due to past conservative stewardship of their forests, which can lead to significant credit yield in the near term.”

Translation: Because many tribes have logged less aggressively than their neighbors, their carbon-rich forests were primed for big payouts of credits. Under Shillinglaw, New Forests or Forest Carbon Partners have helped to secure tens of millions of dollars’ worth of credits for native tribes.

Among the 13 New Forests projects that CarbonPlan researchers were able to analyze, between 33% and 71% of the credits don’t represent real carbon reductions. That’s nearly 13 million credits at the high end.

“Although we cannot prove that New Forests acted deliberately on the basis of our statistical analysis, in our judgment there is no reasonable explanation for these outcomes other than that New Forests knowingly engaged in cherry-picking behavior to take advantage of ecological shortcomings in the forest offset protocol,” said Badgley, the lead researcher.

New Forests managed the first official project in California’s program, registering 7,660 acres of forest land on or near the Yurok Reservation, which runs more than 40 miles along the Klamath River near the top of that West Coast cluster of projects. The state issued more than 700,000 credits to the project for its first year, worth $9.6 million at recent rates.

State officials have pointed to the tribe’s participation as a triumph of the program. In 2014, the board released a promotional video that showed the meticulous work of measuring trees in the Yurok project. James Erler, the tribe’s then forestry director, explained how offsets enabled the tribe to reduce logging. Near the end of the video, Shillinglaw appeared in a sunlit forest, wearing a collared shirt and a New Forests–branded jacket.

“It’s a beautiful watershed,” Shillinglaw said over footage of a running stream and an elk standing before a thicket of trees. “This is the Yurok Tribe’s ancestral homeland and, in part due to the carbon market, will be managed through a conservation approach.”

CarbonPlan estimates the project earned more than half a million ghost credits worth nearly $6.5 million.

Here’s why the researchers say it was overcredited:

The boundary dividing California’s coastal and inland regions runs through the middle of the reservation. The carbon-rich forests on either side of that line are similar, filled with large Douglas firs like most of the coastal region. But more than 99% of the forest designated for preservation falls within the inland zone, where average carbon levels are much lower. The fact that the project was located in the most carbon-rich area of that zone enabled the landowners to earn an exaggerated number of credits.

The fact that the carbon-rich project fell in a region with far lower carbon averages may have produced more than half a million credits of dubious climate value.

At least one person involved in the Yurok Tribe’s forest offset efforts was aware of how geographical choices swing the credits that can be earned.

Erler said during a 2015 presentation at a National Indian Timber Symposium that the tribe had the “distinct pleasure” of having the boundary run through its territory.

“You can take the same inventory data and apply it to the California Coast”—the region to the west—“and it doesn’t come out with the same numbers as you do if you cross the street,” Erler said at the conference, captured in a YouTube video posted to the Intertribal Timber Council’s channel. “Vegetation may be the same, but it changes.”

Badgley said that while the researchers can’t speak to the intentions of any actors involved, it’s clear that this project “benefited from overcrediting and that the Yurok Tribe’s forester was aware how the specific aspects of the protocol rules our study criticizes led to beneficial outcomes.”

Erler didn’t respond to a list of emailed questions.

In an emailed statement, Yurok spokesperson Matt Mais said that the property was the only land the tribe had available to enroll at the time and strongly denied the tribe engaged in any sort of gaming of the system. He didn’t respond before press time to a subsequent inquiry asking why the rest of the tribe’s land wasn’t available for the offset program.

Over the last decade or so, the tribe has slowly reacquired tens of thousands of acres of its ancestral territory, in and around the watershed of Blue Creek and other streams that sustain migrating salmon, from the Green Diamond Resource Company, a major Seattle-based timber business. The complex multistep land deals were done in partnership with the nonprofit Western Rivers Conservancy and financed through government grants, philanthropic donations, and the sale of the tribe’s offset credits.

“As we have recovered additional forestlands, we have enrolled additional acreage in California’s climate programs in support of our Tribe’s strategic goals including protecting salmon habitat, sustaining the revitalization of our cultural lifeways, and facilitating economic self-sufficiency,” Mais wrote.

“It’s insulting to claim that the Yurok Tribe has ‘gamed’ or ‘exploited’ California’s climate regulations,” he added. “Equally important, it’s concerning that elite institutions now criticize us for legally and ethically using a program that was created to protect mature forests and then using those funds to purchase and restore more forest land that was, at one point, ours.”

New Forests defended its practices in emailed responses to questions, arguing its projects have preserved existing carbon stocks and removed CO2 from the atmosphere through subsequent tree growth “as confirmed via third-party verification.”

In a statement, the company said it has worked on projects in numerous areas, not just along the program’s regional boundaries. The company said its projects “have protected and will enhance carbon storage on hundreds of thousands of acres of forests,” adding that one project with the Chugach Alaska Corporation enabled the permanent retirement of a significant portion of the coal reserves in the Bering River Coal Field in southeastern Alaska.

New Forests follows the board’s “scientifically accepted regulations to both the spirit and letter of the program,” the company said in a subsequent statement. “New Forests is proud of the forest carbon projects we have developed under California’s climate programs—they have generated positive environmental impact and furthered the economic and cultural objectives of the family forest landowners and Native American tribes with whom we have worked.”

New Forests didn’t respond to numerous additional inquiries, including direct questions about whether it was gaming the rules of the program.

In an emailed response, CarbonPlan stressed that its paper criticizes the design of the program—not the Yurok Tribe or other landowners. Nor does it allege anyone has broken the rules. Its analysis doesn’t consider or depend on the intent of any forest owners, who can benefit from flaws in the rules whether they intended to or even know about them.

“We recognize the injustices experienced by the Yurok Tribe, including the seizure of their historical lands by the United States government and its citizens,” the nonprofit stated. “We also recognize the Yurok Tribe’s legitimate interest in securing resources to repurchase lands that previously belonged to the Tribe and its people.”

[ad_2]