travel

travel

The city is happy outside Havana’s Hotel Nacional: this Spanish-based port is celebrating its 500th anniversary. Vintage Bel-Airs and Buick convertibles, polished in gumdrop colors, ply the roads. The midnight sky is filled with fireworks and cannon fire, and music pulses in the bars on Obispo Street. Locals dance and drink rum along Calle Galiano, bridged by white and blue LED networks evoking stellar constellations. The dome of the newly restored Capitol shines like a polished helmet on the frontier of Habana Vieja, Old Havana.

Seven flights below me, a bandstand floats in an island of floodlights in the square visible from my window. Around midnight this square will be packed with 100,000 people, dancing to a free concert on the quinquennial anniversary.

Five flights down, meanwhile, is the business center of the hotel on the mezzanine of the National. The frosted glass doors are stenciled with the letters of jazz gold: INTERNET. And as their old desktop computers remind me, I’m here to celebrate an anniversary.

At the dawn of the internet era, twenty-five years ago, I set off to travel around the world–from Oakland, California, to Oakland, California–without boarding an airplane. I performed a minor miracle along the way: I submitted the first travel blog posts ever written on the World Wide Web.

In this milestone, Cuba feels like a suitable place to ring. The country is one of the least internet-friendly places on the planet, with less than 40% of its citizens having access to the Web through strict censorship by the government. But even this is a sharp contrast to 1994 when, on my round-the-world trip, the words “World Wide Web” drew puzzled looks from nearly everyone I met. Nevertheless, the relative isolation of Cuba from global netsurfing addiction reminds me of those pioneering days.

But unlike my four previous visits to the island, I won’t need the hotel’s hibernating desktop dinosaurs in its business center. As the nation’s paying guest, I was given a tongue-twisting username and password that helps me to get online from the comfort of my room when the stars align.

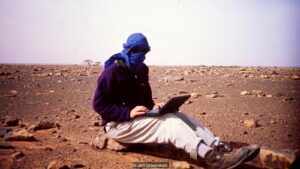

I was a guy with a dream back in 1993 and 1994, during my nine-month global odyssey. O’Reilly Media, a well-known publisher of data science guides, asked me to send back from different stops along with my real-time journey stories. I was carrying one of the first (maybe the very first) ultra-portable laptops during that journey. The OmniBook 300, made by Hewlett-Packard, was a lightweight, super-light marvel running on both AA batteries and AC. It had an excellent pop-out keyboard and an integrated modem.

O’Reilly (one of the first organizations to ever have an online presence) created the Global Network Navigator website. It decided to post my dispatches under the name of “Big World” on its website, linking each story to its position on a world map. You’d see the article, click on the nation. Today, the page could be created by a chimpanzee, but it was a milestone in 1994. Mosaic, the browser that popularized and user-friendly the World Wide Web, was released just months before I left.

The Wild West was the internet; for $20, I could have ordered “pizza.com.” No one had ever written travel diaries on the internet before. You could count the number of sites on the Web back in those days (a list that included The Exploratory, Doctor Fun, and Chabad). But there was no such thing as a travel “blog”-for another four years, the term “weblog” would not be coined.

So I went off to a world where email was still a novelty. It was easy to write about the OmniBook. When I tried to send my dispatches home from distant places like Dakar and Lhasa, the hard part came. My first story was entitled One Hundred Nanoseconds of Solitude, posted from Oaxaca on January 6, 1994. It took two days to relay it back to Big World, during which I visited the city’s main telecommunications office and babbled with its technicians (I didn’t speak Spanish), finally finding someone who found out how to deliver my 2,500-word fax, without pictures, to California through the phone lines.

The process of finding secure enough internet connections around the world to upload each of the twenty dispatches I ultimately posted was maddening. But it was deeply immersive as well. Sending a blog in 1994 was an adventure: It forced me to interact with people I wouldn’t be looking for during an ordinary journey. I had contacts with local telecom administrators (Turkey), diplomats (China), tech engineers (Kathmandu), and even ship captains (the Ursus Delmas, crossing the Atlantic) in my scattered call ports. We were all entertained by what I did. The idea of posting travel stories on the Web was utterly new, and few people thought it was going to catch on – but if it did, everyone saw the potential.

I think everyone, including me. Little did I know as I was sipping Mexican hot chocolate with the head of the data services branch of Oaxaca as my first article was published, that more than half a billion blogs would be on the Web a quarter-century later – with hundreds of thousands focused on traveling alone.

I missed the particular boat somewhere (although I found a freighter to take me home back to Oakland from Hong Kong). I continued to publish dispatches for various online publications throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. But I have never been able to position myself as a qualified blogger. I never thought of “branding” myself or even making a lot of noise about my relatively small e-footprint, through pioneering. I seldom published travel posts as 2010 came around. Elsewhere, the pebble ripples I’d thrown into the World Wide Web have become a tsunami, with some travel bloggers (and their smartphone followers, influencers of Instagram) making small fortunes.

When I took a Coke from the minibar of my mini-suite (one of the very few American brands that you will see in Cuba) and blended it with some Havana Club, I wondered: Why did I stop? I guess it’s because I was inspired in the first place to fly. It’s not just about relaxation, but about destruction as well.