technology

technology

[ad_1]

Inside the probe will be a single instrument weighing only two pounds. There is no camera on board to take images as the probe falls through the clouds of Venus—there simply isn’t the radio power or time for it to beam much back to Earth. “We have to be very, very frugal with the data that we’re sending back,” says Beck.

It is not images scientists are after, however, but a close-up inspection of Venus’s clouds. That will be provided by an autofluorescing nephelometer, a device that will flash an ultraviolet laser on droplets in Venus’s atmosphere to determine the composition of molecules inside them. As the probe descends, the laser will shine outwards through a small window. It will excite complex molecules—potentially including organic compounds—in the droplets, causing them to fluoresce.

“We’re going to look for organic particles inside the cloud droplets,” Seager says. Such a discovery wouldn’t be proof of life—organic molecules can be created in ways that have nothing to do with biological processes. But if they were found, it would be a step “toward us considering Venus as a potentially habitable environment,” says Seager.

Only direct measurements in the atmosphere can look for the types of life we think could still exist on Venus. Orbiting spacecraft can tell us a great deal about the planet’s broad characteristics, but to really understand it we must send probes to study it up close. The attempt by Rocket Lab and MIT is the first with such a clear focus on life, although the Soviet Union and the US sent probes to Venus in the 20th century.

The mission will not look for phosphine itself because an instrument capable of doing so would not fit in the probe, Seager says. But that could be a job for NASA’s DAVINCI+ mission, set to launch in 2029.

NASA /ARC VIA RESEARCHGATE

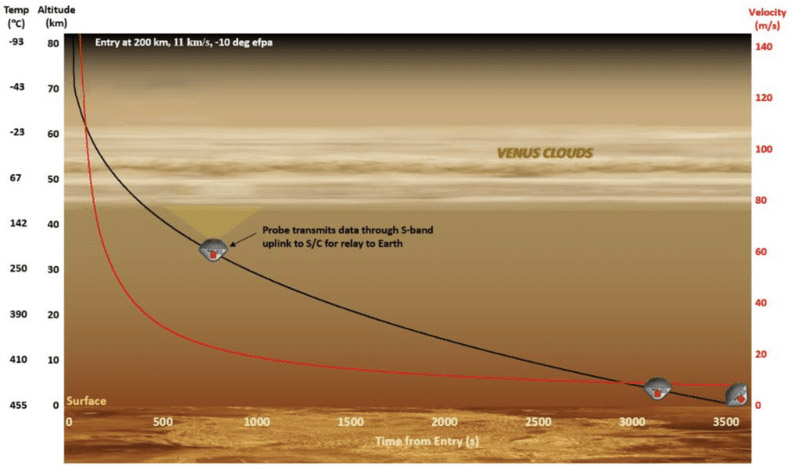

The Rocket Lab–MIT mission will be short. As the probe falls, it will have just five minutes in the clouds of Venus to perform its experiment, radioing its data back to Earth as it plummets towards the surface. Additional data could be taken below the clouds, if the probe survives. An hour after entering the atmosphere of Venus, the probe will hit the ground. Communications will probably be lost some time before that.

Jane Greaves, who led the initial study of phosphine on Venus, says she is looking forward to the mission. “I’m very excited about it,” she says, adding that it has a “great chance” at detecting organic materials, which “might mean life is there.”

Seager hopes this is just the start. Her team is planning future missions to Venus that will be able to follow up on results from this tentative glimpse into the atmosphere. One idea is to place balloons in the clouds, like the Soviet Vega balloons in the 1980s, which could carry out longer investigations.